“Today teaches tomorrow a lesson” – African Proverb

Canada’s History of Segregation

Canada has always been considered a forward thinking land of freedom; a multicultural society where all citizens are free from racial discrimination. Historically, while Canada did not have segregation (Jim Crow) laws like in the United States, segregation did exist in this country. One such incident was a Supreme Court ruling in 1939 where the Court allowed private businesses to discriminate.

In 1936 on July 11th, Fred Christie entered a bar with his friends in Montreal and was refused service because he was a Black man. Christie sued the bar and won his case. The bar appealed and the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that any bar and restaurants had a right to refuse service to any person.

There are other instances of racial segregation throughout Canada. Canada’s military had a segregated all Black Battalion (1916) and the Armed Forces denied Black volunteers until 1939. All of the 48 Black Communities in Nova Scotia were geographically segregated from cities and town. In 1946 Viola Desmond was arrested for sitting in the “whites only” section of a Movie Theatre. Other forms of segregation included housing and apartment rental. Orphanages could segregate children on race, and hospitals could refuse Black physicians and patients. Cemeteries, such as the one in St. Croix, Nova Scotia, could deny burial rights.

Several provinces including Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia had segregated schools. It was not until the passing of the 1977 Canadian Human Rights Act that these practices began to change and the last segregated school in Canada closed in 1983 just outside Halifax, in Lincolnville, Nova Scotia.

Hartley Gosline

Born in Saint John, New Brunswick in 1949, Hartley Gosline was the first Black Canadian to serve in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. As a very young boy growing up, Gosline expressed his strong desire to be a police officer. Although he was told there were no Blacks in the RCMP, Gosline was encouraged and motivated by his mother to never give up and to follow his dream. Graduating from high school in 1968, Gosline with support from community entered training at the RCMP academy in Saskatchewan. His tenure was not without many challenges, including racial slurs. The book by Craig Smith entitled “You Had Better Be White by Six A.M

The African Canadian Experience in the RCMP and Canada’’ recounts an incident where a drill corporal said to Gosline during inspection on parade square --“Gosline, you stick out. You make our troop look bad and you better be White by 6 am.”

There were those in his troop and other instructors who supported him and Gosline graduated as a member of the RCMP in 1969. His first posting was to the New Glasgow, NS detachment and later he was stationed in the historic Black community of North Preston, NS. One day while on duty he was stopped by an elderly man who hugged him and tearfully told him that he never thought he would live to see a Black RCMP officer. Constable Gosline served at other locations during his career including Toronto, Jasper and Edmonton. He left the force in 1978 and says he never forgot those who inspired and supported him to fulfill his dreams and to open the door so that others could follow to become RCMP Officers throughout Canada.

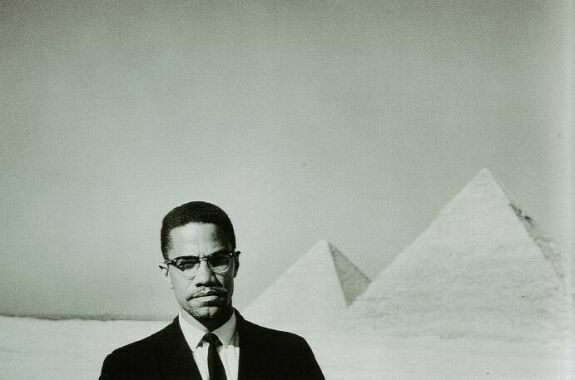

Malcolm X

Malcolm X aka El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz in Egypt, Africa, with the Pyramids in the background, during his pilgrimage in 1964.

Every year people around the world remember the late great African American rights activist Malcolm X, who passed on February 21, 1965 while giving a speech to the Organization of Afro-American Unity in Manhattan’s Audubon Ballroom, New York.

Also known as al-Hajj Malik al-Shabazz, Malcolm X was one of the most dynamic, influential activist in the struggle for human rights for people of African descent. Born in 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska, he preached what was known as a radical message during a tumultuous time in history of the USA. In his early career, Malcolm called for Black people to take up arms to defend themselves against police brutality and the crimes being committed against them across the United States of America. Early in life, at the age of 6 years, Malcolm had experienced violence when his father was murdered, supposedly by white supremists. Living in foster homes through his teen age years, Malcolm was sent to prison for a series of crimes at the age of 20 years in 1945. It is while imprisoned that Malcolm developed a keen desire to read and to study and eventually he embraced Islam. Upon his release, he quickly rose in the ranks to be second in command to the leader of Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad. His message was one of separation and black supremacy. A powerful speaker, Malcolm organized temples across the United States and was recognized around the world as one of the premier African American leaders. He travelled widely to Africa, and the Middle East and it was during his pilgrimage to Mecca, that Malcolm began to change his views.

Writing on his experiences during the Hajj, Malcolm X wrote: ‘There were tens of thousands of pilgrims, from all over the world. They were of all colors, from blue-eyed blondes to black-skinned Africans. But we were all participating in the same ritual, displaying a spirit of unity and brotherhood that my experiences in America had led me to believe never could exist between the white and the non-white. America needs to understand Islam, because this is the one religion that erases from its society the race problem. You may be shocked by these words coming from me. But on this pilgrimage, what I have seen, and experienced, has forced me to rearrange much of my thought patterns previously held.’

This year, 2015 marks the 50th anniversary of the death of Malcolm X. Although he was only 39-years-old, his name remains in history as one of the most influential and outspoken activists of the 20th century, honored throughout the world by people of all colors and creeds.

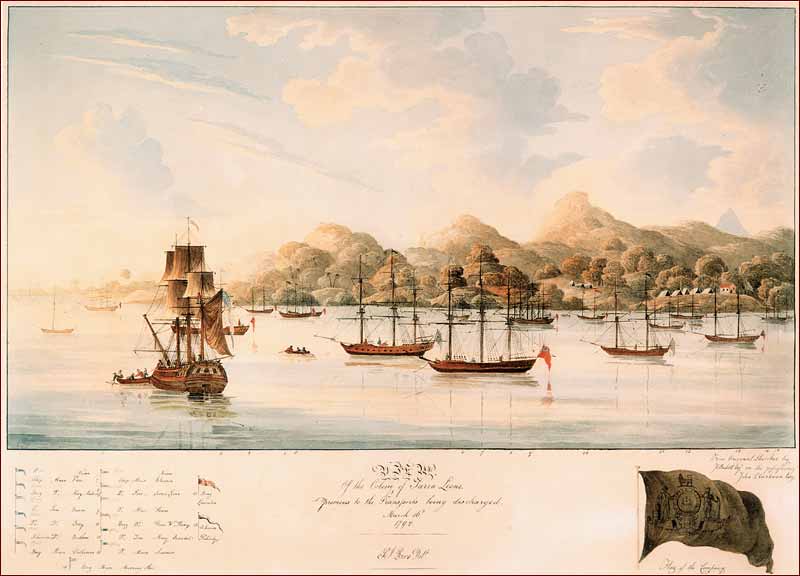

Departure for Sierra Leone

This watercolour view of the harbour at Freetown shows some of the 15 vessels that made the voyage from Nova Scotia during the winter of 1792. Courtesy of Robert G. Kearns, private collection, Toronto.

The Nova Scotia–Sierra Leone Connection: The Black Loyalists of Nova Scotia

There is a Canadian myth about the Loyalists who left the United States after the American Revolution for Canada. The myth says they were upper-class citizens of European descent devoted to British ideals, transplanting the best of colonial American society to British North America. In reality, more than 10 per cent of the Loyalists who came to the Maritime Provinces were Black and had been enslaved.

During the American Revolution, in which the future United States fought for its independence from Britain (1781 to 1784), tens of thousands of refugees were forced to flee. Because they were loyal to Britain, they were called "Loyalists." Many of these Loyalists were Blacks who had been promised their freedom if they would fight on the British side

The response was overwhelming as some 30 000 Blacks escaped to British lines. Many served in the war as soldiers, laborers, ships' pilots and cooks.

One of the 3,500 free Black Loyalists taken to Nova Scotia after the revolution was Thomas Peters. Thomas Peters was with a militia unit known as the Black Pioneers. He was given charge of the Annapolis County Blacks, and he settled with more than 200 former Pioneers in Brindley Town, near Digby. Although Loyalists were entitled to three years’ worth of provisions to sustain themselves while establishing homes and farms, the Annapolis County Blacks received enough to last only 80 days and, unlike the whites, were required to earn their support by working on the roads.

Many Black Loyalists landed at Shelburne, in southeastern Nova Scotia, and later created their own community nearby in Birchtown. With a population of more than 2,500, Birchtown was the largest settlement of free Blacks outside Africa. Others settled around the colony and in New Brunswick.

Most of the Black Loyalists never received the land or provisions they were promised and were forced to earn meagre wages as farm hands or domestics. They suffered in a climate far colder than what they were used to and from unfair treatment from the authorities.

Black workers were not paid as much as White workers. In July 1784, a group of disbanded White soldiers destroyed 20 houses of free Black Loyalists in Shelburne in what was Canada's first race riot, because the Black Loyalists who worked for a cheaper rate took work away from the White settlers.

Many of those who did not have a trade had to indenture themselves or their children to survive. Indentured Black Loyalists were treated no better than enslaved persons. Slavery was still legal and enforced in Nova Scotia at this time. People could still be bought and sold until 1834, when slavery was abolished in the British Empire.

One of the biggest fears of Black Loyalists was to be kidnapped and sold in the United States or the West Indies by slave traders, who sometimes sailed along the coast of Nova Scotia. At the same time, since Nova Scotia did not have a climate to support the plantation system, many White Loyalists abandoned their slaves because they could not afford to feed them

The Black Loyalists realized that the dream of a Promised Land, with freedom and security for their families, was not being fulfilled. Some of the Black Loyalists of Brindley Town, outside Digby, met and decided to send a representative to England with a petition asking the British government for the land they had been promised.

They gave that responsibility to Thomas Peters. He was given power of attorney by several hundred blacks in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to represent their case, and by November, “at much trouble and risk,” he had made his way to London. There he met the abolitionist Granville Sharp, who arranged for him to present his petition to the secretary of state for the Home Department, Henry Dundas.

One of the documents Peters sent Dundas outlined the general grievances of the Black Loyalists, noting that the rights of free British subjects, such as the vote, trial by jury, and access to the courts, had been denied them. The other gave a detailed account of their futile efforts to obtain land. Peters was told that the Black Loyalists would receive free land if they were to settle in Sierra Leone. He returned to Nova Scotia with Lieutenant John Clarkson of the Royal Navy, to convince Black Loyalists to leave Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

On January 15, 1792, 1196 Black Loyalists, including the notable leaders David George, Boston King, and Moses Wilkinson, left Halifax in fifteen ships, for Sierra Leone. This was slightly less than one third of the number of Black Loyalists who had arrived in Nova Scotia in 1783.

The Krios of Sierra Leone

The Krios are a distinct ethnic group in Sierra Leone. They are the descendants of Black Loyalist, The Nova Scotia Maroons and Liberated African slaves who settled in the Western Area of Sierra Leone between 1787 and about 1885. The colony was established by the British, supported by abolitionists, under the Sierra Leone Company as a place for freedmen. The settlers called their new settlement Freetown. Today, the Krio comprise about 4% of the population of Sierra Leone.

Krio culture is primarily westernized. The Krios developed close relationships with the British colonial power; they became educated in British institutions and held prominent leadership positions in Sierra Leone under British colonialism. Much of the Western attributes of Krio society came from the "Settlers" in Sierra Leone. They were called the Nova Scotians or "Settlers" and they founded the capital of Sierra Leone in 1792.

The vast majority of Krios reside in Freetown and its surrounding Western Area region of Sierra Leone.

The Krios developed what is now the native Krio language (a mixture of English and indigenous West African languages). It has been widely used for trade and communication among ethnic groups and is the most widely spoken language in Sierra Leone. Due to their history, the vast majority of Krios have English surnames. Many have both English first names and last names.

On March 11, 1792, when the Black Loyalist disembarked from the 15 ships that had carried them from Nova Scotia to Sierra Leone they gathered under a large Cotton Tree not far from the harbour. As the Settlers gathered under the tree, the Settler preachers held a thanksgiving service. After the religious services, the settlement was officially established and was designated Freetown. Today, the Cotton Tree stands as a national monument and is protected by a cemented enclosure.

The historical ties and the factual evidence indicate that the Black Loyalists were instrumental and the pivotal element in the formation of the new colony of Sierra Leone. Sierra Leoneans honor the memory of the Nova Scotia connection in a variety of ways. For example – in the naming of streets in tribute to several of the originals who came from Nova Scotia. This includes Lightfoot Boston Street (Henry Josiah Lightfoot Boston) and Wilkinson’s Road (Moses Wilkinson). In Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, stands a statue of Thomas Peters, in tribute to the Nova Scotians. Elementary and Junior school history and social studies curriculum have content on the Nova Scotians and in the older city neighborhoods one can see what are called the Nova Scotian Krio houses because the roof is slanted (a design used by the Settlers when they were here in Nova Scotia).